As witness, and a designer doing artistic research, in the shadow of Yiddish culture between languages in Europe, the course Witness and Documented Memory was conducted with second year BA students in visual communication design.

In my introduction to the project, Witness and Documented Memory, I seek to provoke a change of mind, with research of intuition, thoughts, and text—from a conceptual abstract dimension to a more concrete visual dimension. My plat form comes from Yiddish and linguistic culture, where I asked: How can ideas within intuition, thoughts and memory of the witnessing be taken care of? How can the thought be an image? How can we transfer what we are witnessing to a documented memory? And what about the things we witness that are invisible?

In between witness and documented of memory

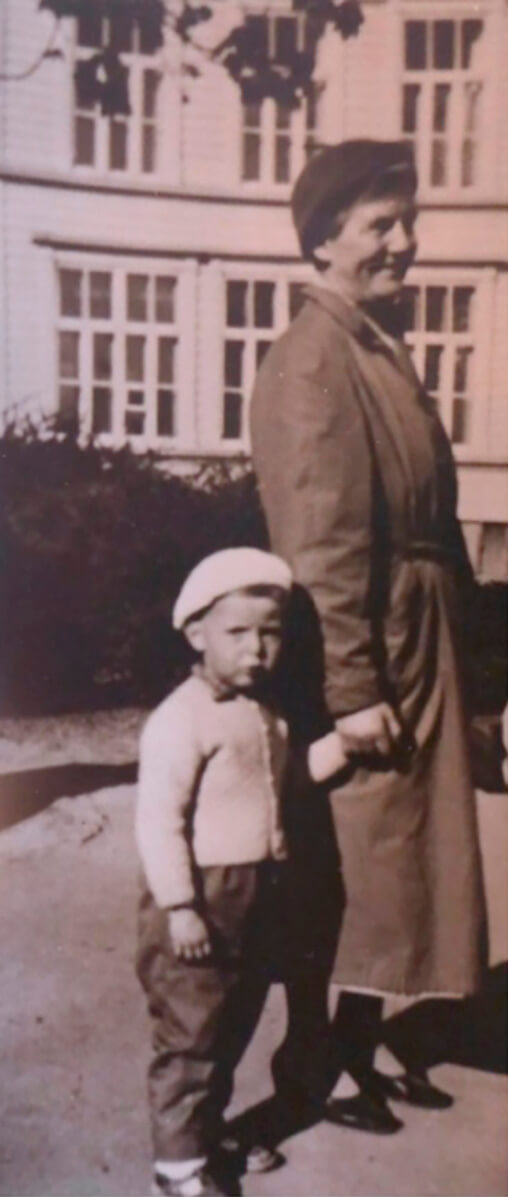

The research based course was from the beginning a project, that started with my life with my grandmother, and turned into an artistic research project. It was mystical and evocative, living next to her in a ramshackle part-shack part-cowshed just above the upper reaches of the shoreline. Among her treasures was a harmonica on which she played for me her own characteristic tunes. Once the possession had captured her, she would augment her playing with songs in an unknown tongue. Years later, after her death, I unraveled enough family history to deduce that this perhaps was likely the last breathful of Yiddish songs played along our stretch of the Norwegian coast.

Mass-claw or Matisklo, a sound image, that no-one understood

What we witness, and which documentation we can trust is very complex and requires methods. A user must have a system, that consists of knowledge. This makes it possible to document. A system of knowledge that can be used intuitively to review and document. A system that is a network to capture what we witness.

In the Danish translation Carsten Juhl has an introduction to Giorgio Agamben’s book Remains of Auschwitz and the Witness (Homo Sacer III), where he talks about Hurbinek’s history. It is about the three year-old boy Hurbinek who was alone in Auszwitch and no one knows his story. And how he repeats the same statement Massclaw, or Matisklo, until his death.

There were a large number of languages used among the prisoners in the camp, but there was no language that gave some knowledge of what Hurbinek said and about what happened to the three year-old boy. The story was found buried in the ground of Auschwitz in a bottle written on paper, seven years after the war ended.

In the Danish journal Semiotics almost 30 years ago, Michel Serres was in conversation about this phenomenon with Per Aage Brandt under the title “Markov and Babel” that language can not be driven by a promise to act as a synthesis, for example, a coherent explanation. We need to search for documents from somewhere else, from the mouth, the sounds and the rehearsal, the memory of the sound, perhaps about the reach of the sound, for a sense of rehearsal. Hurbinek said Masseclo or Matisklo and the soundtrack was a testimony with a closeness to what was happening in his mind, his feelings, and from his point of view. Can we copy Hurbinek and his language being repeated as a documentary? In documentaries we must be true to what we are witnessing, we must know how we can repeat it directly and maybe just understand something. As a witness, many values and invisible elements are transformed into a form that documents the unknown.

Letters to an unborn child in between languages

From Roman times to 1930, identity has been linked to where you lived: where you belong. With the establishment of the European-nation-state, many became identityless. The harmonious coexistence of the European people was then divided, because Europeans thus confessed that their weakest members were forever excluded. The few refugees who insist on telling the truth, even when it is “inappropriate”, in return for their unpopularity, offer an invaluable advantage: History is no longer a closed book, and politics is no longer the exclusive privilege of the Jews (Hannah Arendt, We Refugees, p.33).

In Norway a large family of twelve is at risk of losing citizenship because the grandparents stated that they were stateless. They had Jordanian citizenship, and they could not have Norwegian citizenship in 1997, and their citizenship was cancelled in May with message from the department of Immigration and Integration.

The law is such today that the authorities define it so that people who have lied about their citizenship can never get Norwegian citizenship. Thus, children and grandchildren who were born and have lived all their life in Norway will be affected. Grandparents of children who received Norwegian citizenship in 1997 are Palestinian refugees, who were detained in a refugee camp in Jordan and therefore had Jordanian identification as refugees, but not citizenship.

Sylvi Listhaug said in a debate in the Norwegian Broadcasting Corporation in 2015: “I respond to the Norwegian goodness of the tyrant who rides the Norwegian society as a ghost.”

Society has discovered disgrace as a powerful social weapon that can kill without bloodshed. Once passports and birth certificates and sometimes income taxes are no longer on formal paper, but have become a means of social distraction; we lose faith in us. If society does not recognize us, we are, and have always been, prepared to pay any price to become a part of society (Hannah Arendt, De retsløse og de ydmygede, p.42).

“Where do the words disappear of the people who talk to themselves on the streets of New York? Do they drop to the pavement as mere dust?”

God Hid His Face Selected Poem by Rajzel Zychlinsky

This makes me cursed, this is unworthy human treatment, and an abuse of laws and regulations. It is vulgar that we should accept that it is both fair and correct when a minister in the Norwegian government, or an authority, says this. Then our documentation of memory, is poor.

Letters to an Unborn Child in between languages

A text loop about the invisible. Images from an installation with film text as a loop on a window at Gallery Room eight in Bergen. The texts were compressed and almost naively addressed to the Minister for Immigration and Integration, Sylvi Listhaug. They addressed pressing issues in four languages. Projected upon the same surface in a loop, they were indecipherable.

The text in the text loop

In English

Unborn child. Always keep your papers clean. Avoid all Sylvi Listhaugs. Embrace your identity. Not knowing where you shall go; I am ever proud of you.

In Yiddish with roman alphabet

Nisht geboyrn kind. Dayne papirn zoln zayn shtendik reyn. Farloz ale Listhaugs. Haldz daynidentitet. Ikh veys nisht vu du geyst, ober ikh shep nakhes fun dir.

In Yiddish with yiddish alphabet

. אךיב יןאלץשטאָלץפ ון א .י נטי גע ווא וסט וווא יר וועט ג יי ן עבמראַסעא ייערא ידע נט יטע.ט Listhaug`s ויסמייַדןאַלע .ש טענד יקהאַלט ןד ייןצ ייט ונגע ןר י.י ן אַנ באָר ןק ינ ד

In Norwegian

Du skal få din tilhørighet og må ikke Listhaug gjøre deg ID løs. Jeg vet ikke hvor du går, men jeg er stolt over deg.

References

- Jidisz far Ale Common title for previous artistic research and practice as platform for the research based education program :

- Learn Yiddisz in 10’ min [Performance]

- Yiddish for ale [Exhibition]

- The pas over— about boarders [Exhibition]

- Walk with Yiddish – Negations and contextualities of an concept of right to imagine [Installation], Gulating Lagmannsrett / Gulating Court of Appeal.

- Letter to unborn Child. [Installation], Inbetween seminar and exhibition

- I miss you Jude (2009) [Installation], Inbetween seminar and exhibition. Coming presentation of artistic research and practice

- Yiddish for ale, In between – Designing for empathy. What is the story today about what was confiscated? [Interactive installation].

Literature:

- Agamben, G. Resterne fra Auswschwitz, Danske Billedkunstskolernes forlag.

- Arendt, H. (2017), De retsløse og de ydmygede. Informations Forlag.

- Arendt, H. (2017) Vi Flygtninge. Forlaget slagmark. Oversættelse og efterord: Flohr, M.

- Graedler, A.L. (2002) UiO Språknytt 3-4

- Levinas, E. (1972), Humanism of the Other. Oslo: Det Norske Akademi for sprog og litterateur.

- McEwan, I. (2001) The Guardian, September 11

- Sebak, P.K. (2008) Vi blir neppe nogensinne mange her Jewish in Bergen 1851–1945, Forlaget Vigmostad & Bjørke AS

- Traktat Democratic National Convention (1930) Council of the League of Nations, (archive United Nations Documents).

- Zychlinsky, R. (1997), God Hid His Face. Word &Quill Press.