Today, we are aware of climate change—and we have been aware of it for some time. There is an overwhelming consensus amongst the world’s leading scientists, and yet our society has been unable to take decisive action. Our lives are virtually unchanged; we continue with our old habits and, to put it mildly, act as though we don’t give a damn.

“Why is that so?” asks Per Espen Stoknes in his book What We Think About When We Try Not to Think About Global Warming: Toward a New Psychology of Climate Action. (Stoknes, 2015).

Stoknes presents statistics demonstrating that the worry about climate amongst Norwegians declined between 1989 and 2013. (2015, p.5). How can it be that concern decreased even while our situation was becoming more precarious? Stoknes calls this “the climate paradox”, i.e. the more information, the less anxiety. As I understand it, the root cause of this problem is largely a communication failure, so perhaps this should be addressed by professionals in visual communication?

“This qualifies as the greatest science communication failure in history: The more facts, the less concern.” (Stoknes, 2015, p.81)

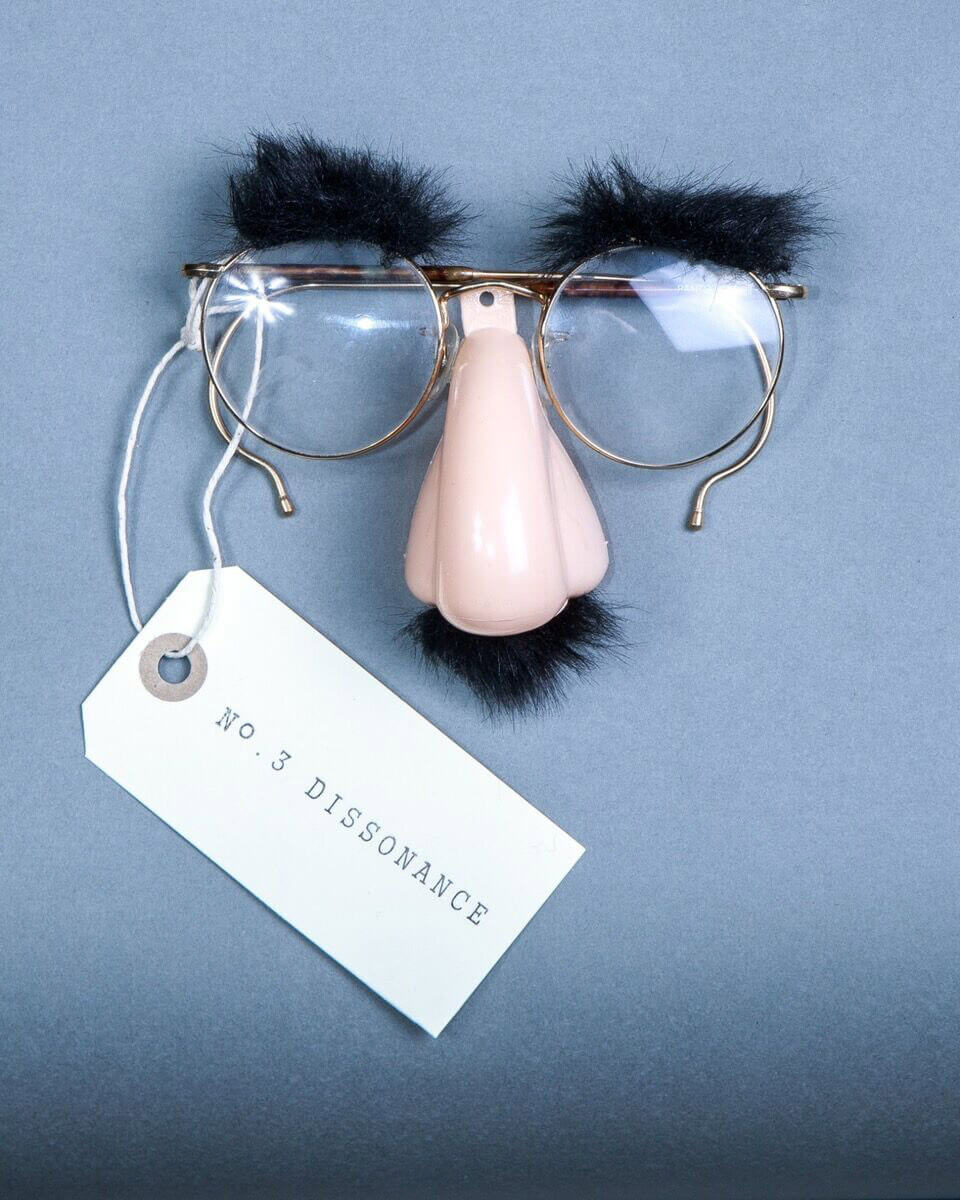

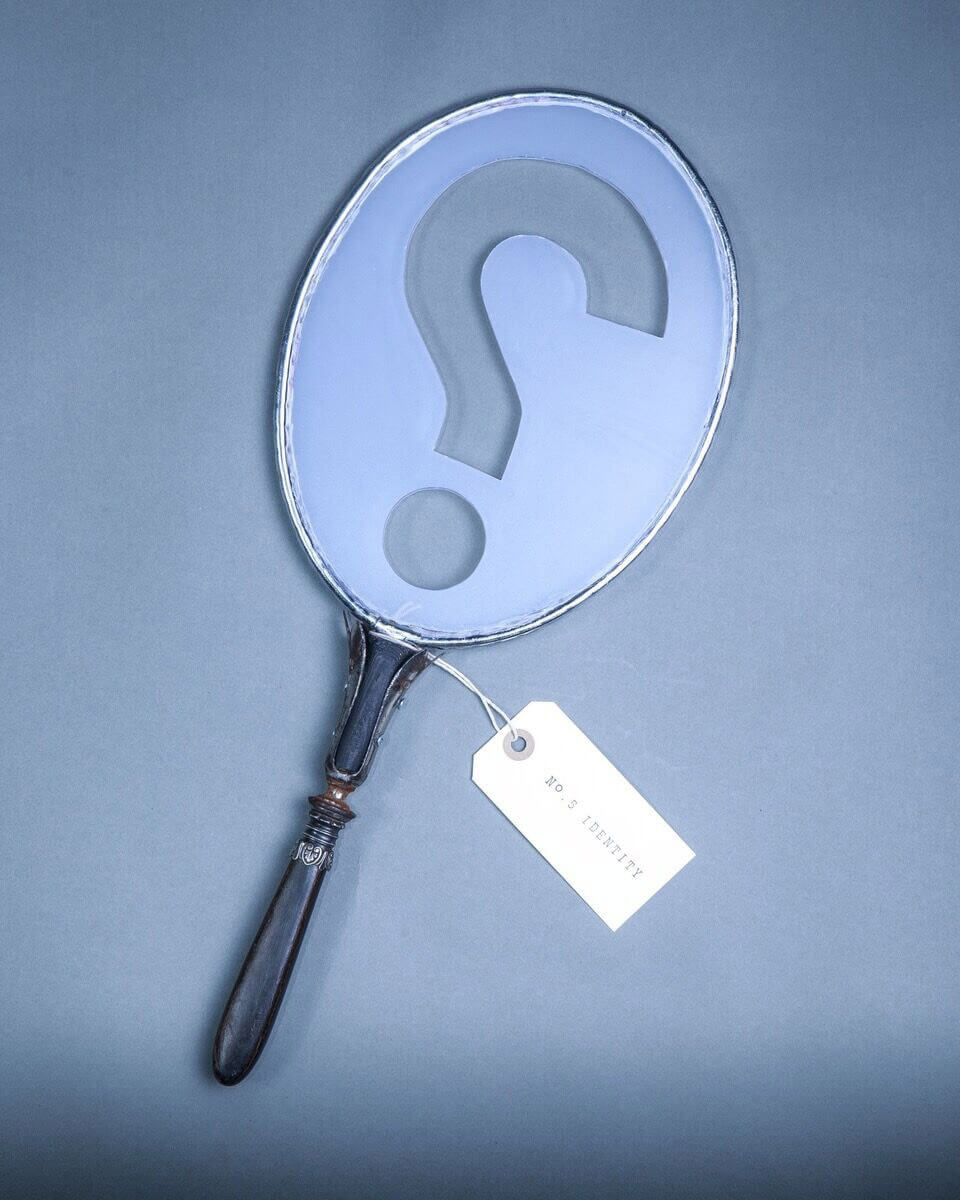

In his book, Stoknes explains our relationship to this environmental message and how five psychological barriers prevent us from truly accepting the message and changing our behaviour. He refers to these five barriers as distance, doomsday, dissonance, identity and denial.

In my project, I seek to describe our psychological condition and these five barriers. My objective is to create a design strategy for better communicating and conveying environmentally important issues. This strategy must take into account individual reactions and avoid triggering the barriers that block us. The overarching goal of the project is to allow each individual to explore and understand their personal relationship to the environmental message, without being burdened by the many negative and unpleasant emotions associated with the aforementioned psychological barriers—emotions such as guilt, impotence and denial.

When considering my design strategy, I examine sustainable design and how the environmental message has been treated and visualised. What strategies must the environmentally-aware designer follow, and which criteria must he or she take into consideration?

“Today, environmental concerns, especially issues of sustainability, are essential parameters in all design practices. However, this green revolution is a glaringly white spot on the design historical map, still awaiting its scholarly historicization. Historical understanding of, and critical reflection on, the rise of sustainability as the primordial trope in design discourse is essential to building a solid knowledge base and to underpin present and future decision-making.” (Fallan, 2014, s.15)

Because environmentally-conscious design is still in its infancy, there is a lack of studies and critical reflections on its historical development. Ketil Fallan addresses this in his essay “Our Common Future: Joining Forces for Histories of Sustainable Design” (Fallan, 2004, p.1). I am convinced that environmental psychology can be a valuable tool for understanding how we have designed so far, as especially for improving such design in the future.

My impression is that the visualisation and design of environmentally themed messages is still rooted in the environmental movement of the 1960s and its activist approach. The Green Revolution has set new ethical standards for design, but not necessarily for its aesthetic aspects.

“Of the traditional criteria for judging design—cost, performance, and aesthetics—the agenda known as sustainable design is redefining the first two by expanding old standards of value. But what about aesthetics? Does sustainability change the face of design or only its content?” (Hosey, 2012, p.2)

Aesthetics have not been considered essential for environmentally-aware design, and have therefore been aproached rather uncritically. My own view is that environmental messages are given such a strong identity that, for better or worse, they unconsciously trigger psychological barriers; by doing so, they exclude people who do not already identify themselves with the politics and culture of the environmental movement.

My goal is to develop an alternative approach, and alternative forms of environmentally-aware design, that make very conscious choices based on the society in which we live. This is why I have chosen to depart from traditional eco-friendly design, which in my opinion has failed to inspire the desired level of engagement. This is due to the way the themes are presented and communicated, and the historical, political and cultural context. The failure is the result of poorly chosen communication over many years, where the content has been dominated by facts, statistics, doomsday prophecies and visual shock tactics.

My strategy has been to work with a more positive framing, while being mindful of Stoknes’ theories of environmental psychology. This entails creating transparency and inviting the recipients to feel a familiarity with the themes. It is imperative to avoid increasing today’s cultural and political polarisation. Hence the objective must be to create a project that can be experienced collectively and socially, where there is a low participation threshold.

This became to me the most important criteria—in fact the only criteria I could follow as an environmentally-aware designer.

The project has resulted in an animated film. The main character shares his feelings, and the challenges and shortcomings of trying to be environmentally friendly. With disarming irony, the film casts light on the aforementioned psychological barriers, and the main character’s environmentally damaging habits, and the inevitable feeling of falling short. The film creates an open psychological space that fosters honesty with oneself, without pointing a moralising finger.

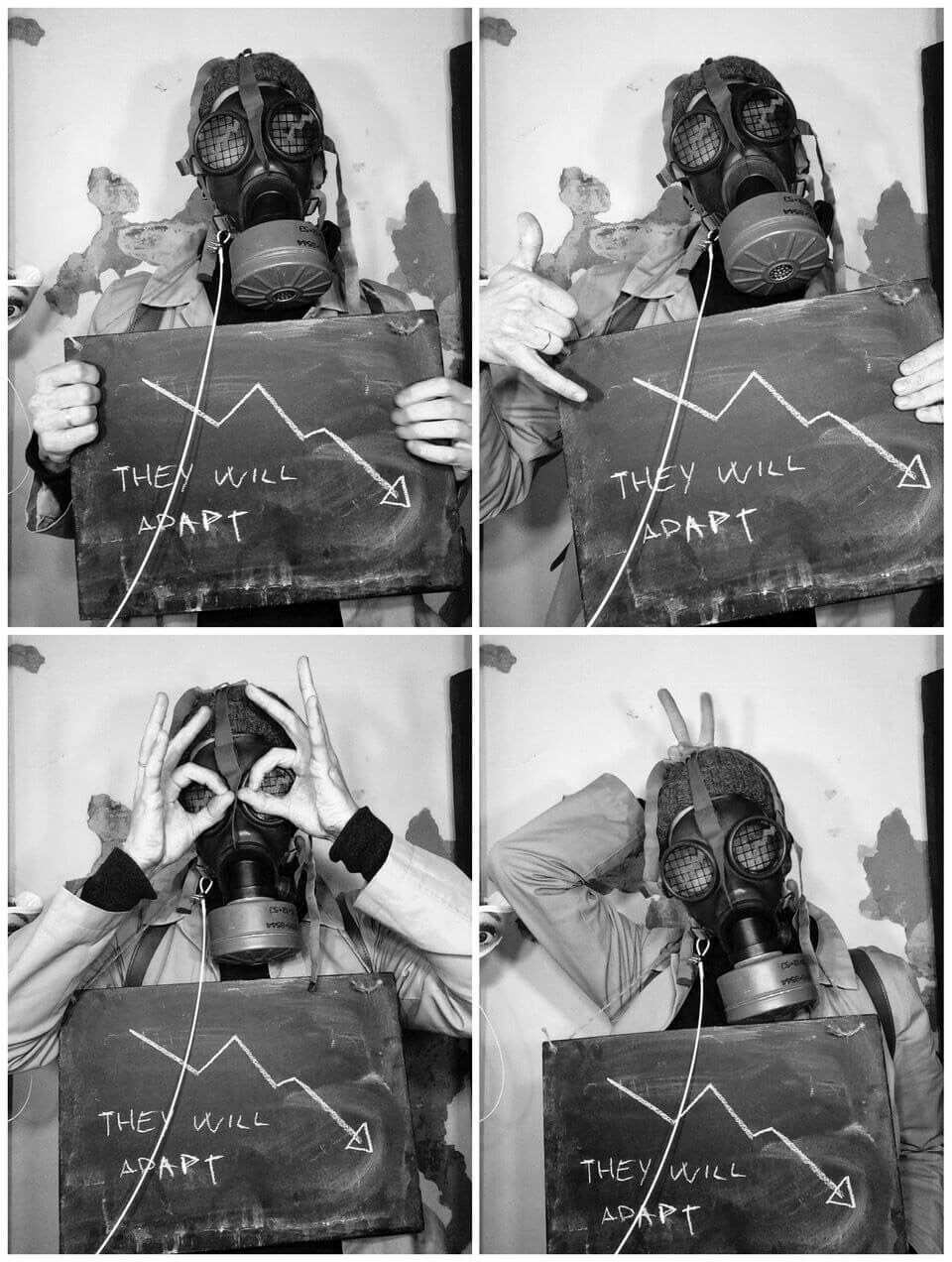

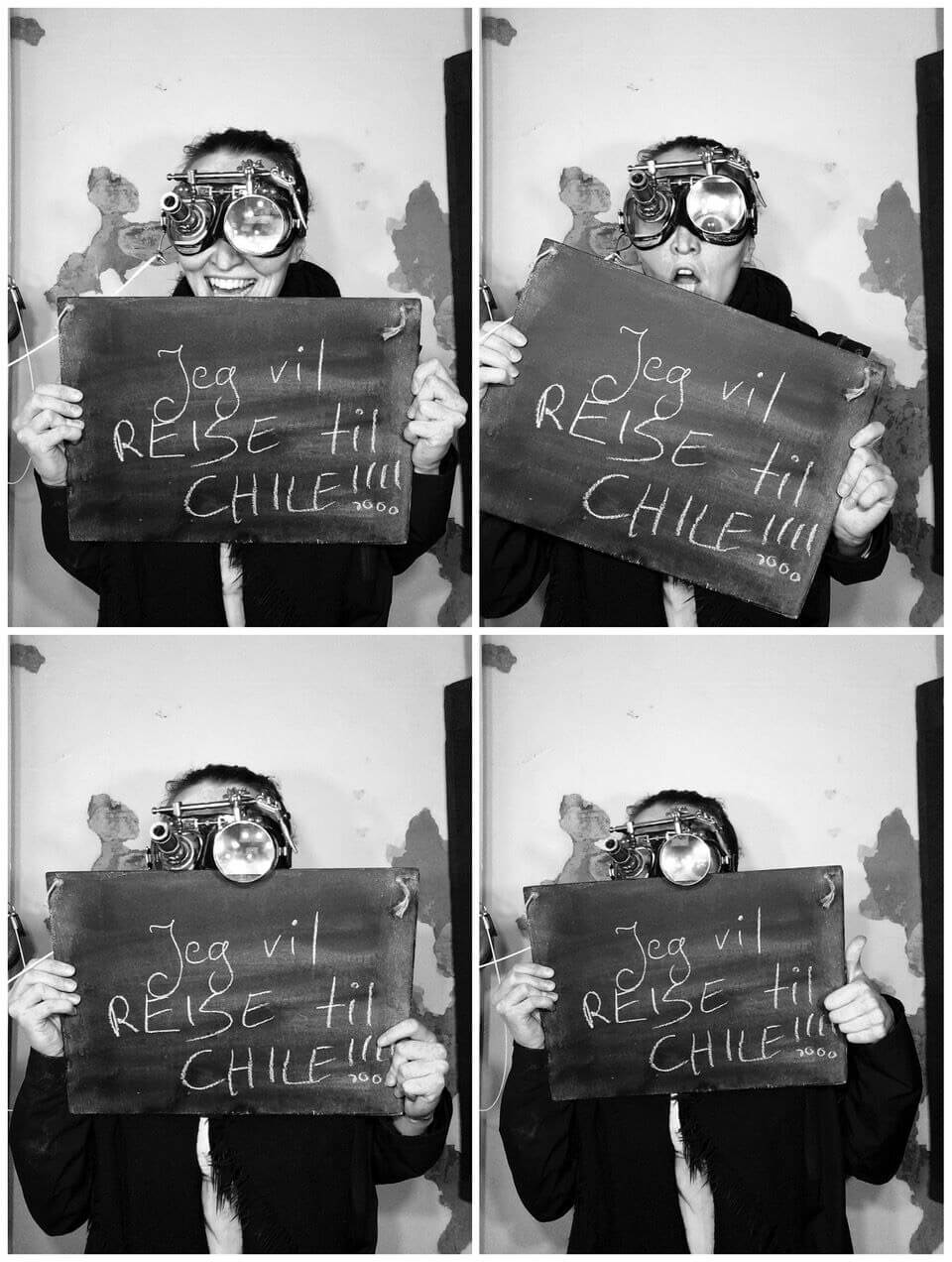

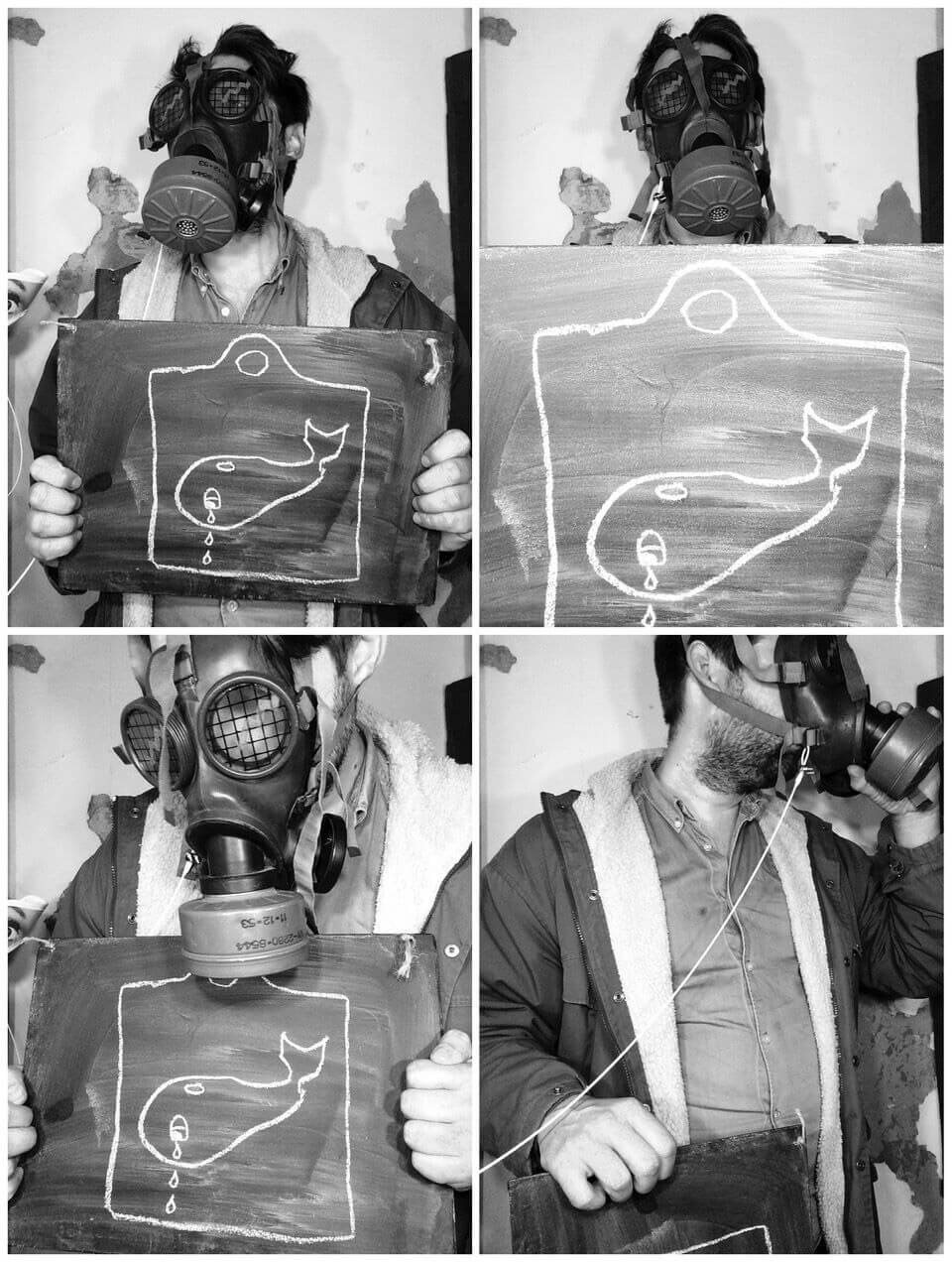

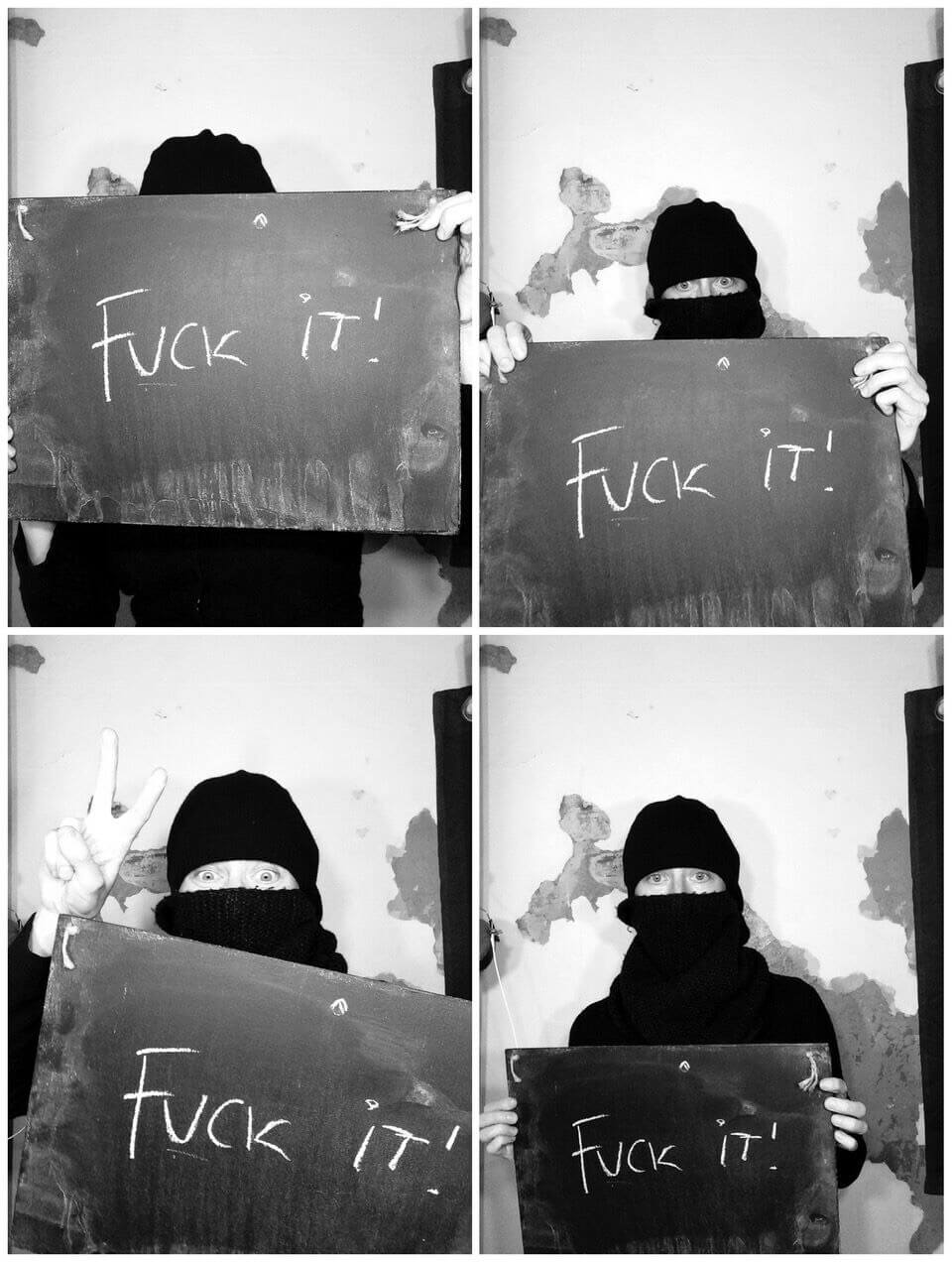

In the animation, the five barriers are given visual form as absurd but recognisable objects. These objects are used as real props while acting as embodiments of those barriers. In addition, they are exhibited in a photo booth where members of the audience are invited to interact with them, comment on their feelings and interpretations, and to take their own picture. These photos are collected, and the audience can browse through this collection and reflect on their own relationship to the environmental message.

The collection clearly has considerable recognition value for members of the audience; the comments are honest, funny and personal. This photo collection can be used to map our the feelings and be an aid in the development of strategies for environmentally-aware design, which I am convinced could be healthier for the individual psyche and truly motivate to both dedication and action.

It is difficult to see progress and find solutions to the environmental challenges that our society is confronting. For the Norwegian, it is also hard to feel the relevance of a problem that we are not experiencing directly, especially while constantly being told that our lifestyle is in conflict with the environmental messages we are being given. In addition, there is the frustration of being told that the efforts you actually are making don’t have any impact. Consequently, the individual is left high and dry feeling massive personal responsibility, confusion, impotence and pessimism.

Information overload, doomsday prophecies and judgemental messaging about people’s lifestyles have failed as a communication strategy. It is therefore vital that environmentally-aware designers reassess their methods and practice. In my opinion, we must take a step back and seek to understand why environmentally-aware design has taken the form it has today. We must redefine our goals and our criteria, which we have all too long taken as givens and which have prevented us from thinking innovatively.

Environmentally-aware design must be developed so that it reaches the point where environmental psychology becomes just as much an integral aspect of the design discipline as the focus on sustainability.

References

- Fallan, K. (2014) Our Common Future: Joining Forces for Histories of Sustainable Design. Tecnoscienza – Italian Journal of Science & Technology Studies. [Internet] 5(2), 15–32. http://www. tecnoscienza.net/index.php/tsj/article/view/201 [Read 12 October 2018]

- Hosey, L. (2012). The Shape of Green: Aesthetics, Ecology and Design. Washington, DC: Island Press.

- Stoknes, P. E. (2015). What We Think About When We Try Not to Think About Global Warming: Toward a New Psychology of Climate Action. USA: Chelsea Green Publishing’.