Abstract

The image of 'the other' is a matter of great importance to solving contemporary and future challenges. Examples of visual representation contributing to compassion and a sound dialogue are needed. There is also a lesson from the past: The core of this text focuses on the atrocities committed by Nazi-German occupants towards the population of the Litzmannstadt ghetto (now Bałuty in the Polish city of Łódz) during the Second World War.

Within Jewish tradition, stones are used to commemorate a deceased person’s grave. Our only knowledge of their existence is through archival material, such as deportation lists. How can we let the world know of their fate and honour their memory?

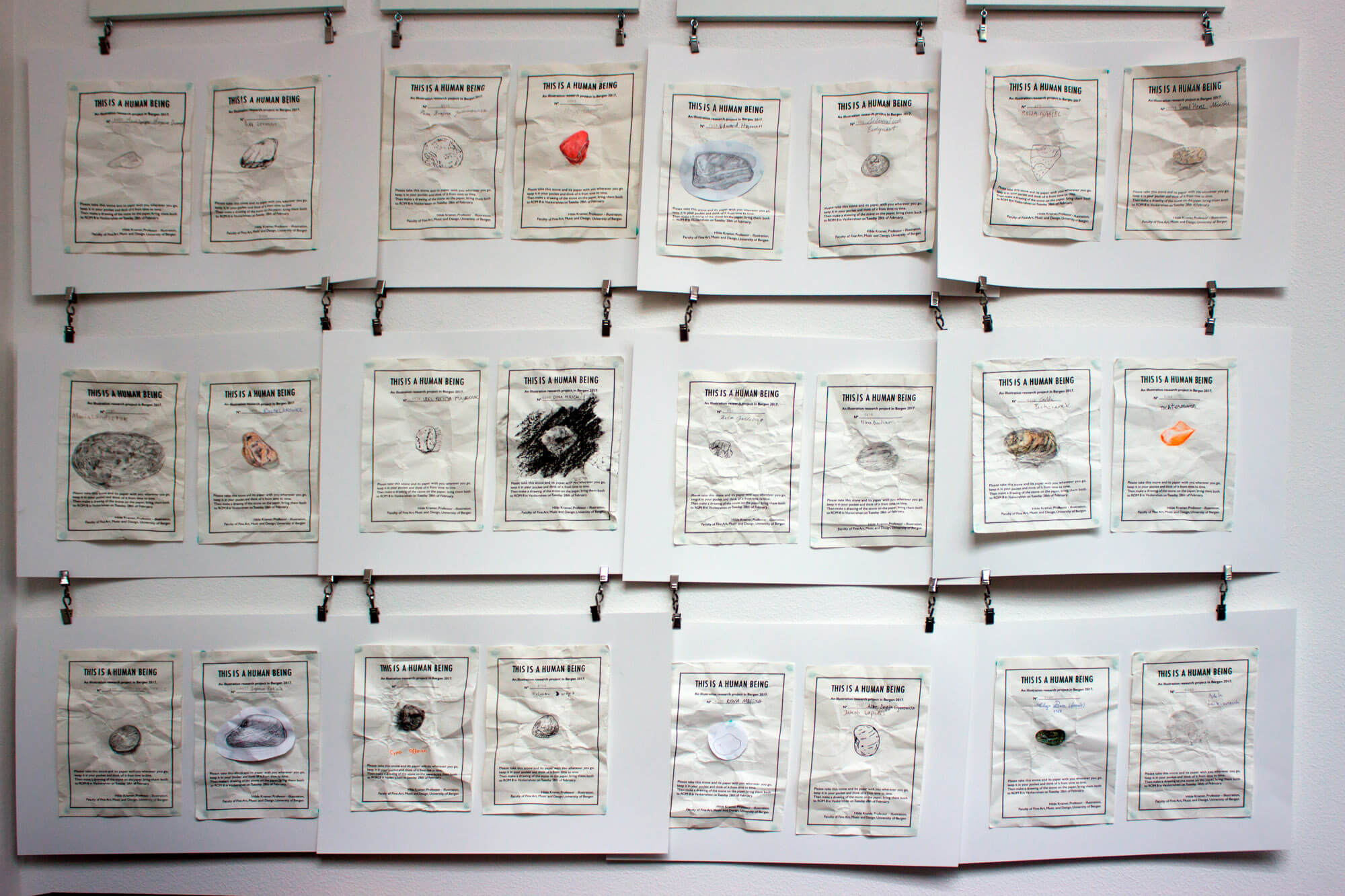

In workshops a gradual unveiling of information takes place; initiated by giving the participants a stone wrapped in paper. The stone is held by the participant during a workshop of drawing; who in return receives information about the name, gender, address, and age of the child commemorated by the stone. Each stone equals a child from Łódz that was deported and murdered. In the final part of the workshop, the stone and the drawing are returned, and then stored in archival boxes for safekeeping before being placed at the Jewish cemetery in Łódz. Participants are asked to fill in a survey about their experiences during the workshop. At a later stage, the drawings will be included in a sequential story about the children of the ghetto.

What is the future of images? In recent years technology has moved in a direction where we no longer are spectators to, but rather become part of the image, such as in VR and AR. But at present, the dominant arena for images is via our phones. The term 'hyper-visual time', in the title here, relates to the stream of images that confronts us every day via the exchange of images with friends and family, on social media, and news channels. The flow of images means access to information about human suffering; images of war, of hunger and fleeing. Seeing such images often lead to raised empathy; a visual nudging to people taking action through social engagement.1 However, it is also a time of hostility towards people seen as 'the other'; migrants constitute one such group. The present rhetoric towards them echoes a dark past; before and during the Second World War, resembling tendencies which almost led to the extinction of Jews, Roma, homosexuals, disabled people, and all political opponents of the Nazi party in Germany. Eight decades after the atrocities, witnesses of the Holocaust are now few. Present and future generations must be informed, thus new ways of reaching their hearts and minds need to be developed.

1 Since I start this article questioning the future, and have already presented some challenges of the past; what does the present look like? We must not forget to tell there are many practitioners from the field of visual communication who use innovating ways of creating understanding for challenged groups. In Journal of Illustration, Volume 4 Number 1 several examples are mentioned.

Our view on others

The concern of this text is how images can foster empathy, the ability to understand or feel the experience of others from their perspective. With Holocaust images, it is not irrelevant what kind of images we use. Instead of waking our compassion, images of humiliation and degradation may lead to what Julia Kristeva calls abjection (Kristeva, 1982), the viewer may turn away in horror because these images represent bodies that resemble one’s own – but as degraded, discarded debris. The artistic research project This Is a Human Being investigates how we may provide the coming generations with images that serve as memory-building and encourage the viewer’s quest for knowledge rather than reporting existing knowledge. Empathy is the key to personal relationships, according to social philosopher Roman Krznaric; to social change, and is an antidote to hyper-individualism (Krznaric 2014). At a guest lecture at KMD in 2017 Krznaric explained how empathy may be divided into affective empathy; shared emotional response, and cognitive empathy; taking the perspective of others. He also used emphasized the ability to think what it might be like to be in the shoes of a person different from ones own. His expressions are parallel to those used by philosopher Martha Nussbaum (Nussbaum 1997).

Since 2016, students from the Faculty of Fine Art, Music and Design at the University of Bergen (Norway), Ostwestfalen-Lippe University of Applied Sciences (Germany), University College of Volda (Norway), the Strzeminski Academy of Art in Łódz (Poland), the Free University Berlin, and representatives from the Polín museum, Warszawa (Poland) and Falstad Center, Trondheim (Norway) gathered at the Marek Edelman Dialogue Center in Łódz for a yearly cross-disciplinary workshop to develop new concepts on memory and commemoration. The project described in this text is one of the outcomes of this cooperation.

A story of forced labour and death

In the weeks following the Nazi-German occupation of Poland, the Jewish inhabitants were forced to move to ghettos all over Poland. Inside the ghetto Litzmannstadt (as the Nazi-Germans named the city of Łódz during World War II), the inhabitants became victims of pillaging from the Nazi-German occupants, and were forced to work under inhuman conditions. The food rations were far below minimum calorie intake to survive. Those too young, too weak or too ill to work were sent to die. From December 1941 to the end of 1942, a minimum of 152,000 prisoners2 were transported from the ghetto by train in cattle wagons, forced to undress, and were then driven to a deserted area in the forest of Chełmno, a couple of hour’s drive from the ghetto, there, in the exhaust fumes from the truck, they were led to a carriage compartment made for killing as many as 80 persons at a time. Jewish prisoners were forced to drag the dead bodies out of the vans to a prepared place where the bodies were burned. The deportations dated between the 5th and the 12th of September 1942 have a special meaning: this was the campaign targeting the Litzmannstadt children.

2 Recent research suggests numbers as high as 225,000 (Montague, 2012:183-188)

I come to you like a bandit, to take away what you treasure most in your hearts! I have tried, using every possible means, to get the order revoked. I tried—when that proved to be impossible—to soften the order. [ ... ] Let this be a comfort to our profound grief. (Foreman Rumkowski’s speech 4th of September 1942, Holocaust Research Project, 2007).

Chaim Rumkowski, the leader of the Jewish council of the ghetto, appointed by the Nazi-German occupants, addressed the inhabitants on the 4th of September 1942 at 4 pm.3 His 'Give Me Your Children' speech (Holocaust Research Project 2007) to the ghetto was horrendous. All children under ten years of age were to be deported. Some days earlier the Nazi-German occupants had emptied the hospitals in the ghetto in the most barbaric manner (Horwitz, 2009, p. 203–205). Now it was the sick and old people’s turn, and children under the age of ten years. At least 15,681 people.4 Only a marginal group of the children from the ghetto were exempted from deportations. The enormous trauma led to an increase of suicides in the remaining population.

3 Many have questioned if Rumkowski understood the consequence of the Nazi-German order. A metaphor used in the speech; ‘cutting off a limb to save the body’, does harbour certain indications.

4 See survivor testimony by Oscar Singer https://www.jewishvirtuallibrary.org/after-the-deportation-of-children-from-lodz-september-1942

The Litzmannstadt ghetto archive as starting point for the project

Unlike most other ghettos, the Litzmannstadt ghetto had a centralized structure of Jewish administration that in 1942 employed 12,000 clerks and other office workers. A daily record of life known as 'The Chronicle of the Lodz Ghetto', was kept between 1941 and 1944, written by a team of authors. They even had two professional photographers to document the daily life of the ghetto, and an archive functioning between January 12th 1941 and July 31st 1944.

At the end, with only 800 people left to prepare for a gentile takeover (and even foreman Rumkowski had been deported to perish in Auschwitz-Birkenau), the archive was still preserved.5 After the war the Litzmannstadt ghetto archive became part of the city archive of Łódz, providing historians researching the Holocaust detailed historical information about all aspects of the daily life in the ghetto.

5 Thanks to a ghetto postman, Nachman Zonabend, who saved a few thousand pages from the ghetto archive. In contrast to most other occupied territories, the material remained relatively intact after the Nazi-German regime was defeated.

Remembering and forgetting

The uncertainty of what we need to remember in order to prepare for the future, results in us fearing oblivion. The accelerating access to information in contemporary societies leads to an increasingly rapid slippage of the present into the past, according to historian Pierre Nora (Nora 1989). 'Memory takes root in the concrete', he claims, using the term 'liéu de mémoire' (site of memory). It is a definition that goes beyond memory as geographical place; though not excluding spaces—in addition to gestures, images, objects or events; all can have special significance related to a group’s remembrance.

In her book Contemporary Art and Memory, author Joan Gibbons divides the concept of memory into five sections (Gibbons 2012, p. 8), based on a classification by the Stanford Encyclopedia of Philosophy:

- autobiography, memory presented as personal narrative, and the implication of making the private public

- the use of objects, photographs and sounds that were part or link to the original memory

- revisionist memories; mapping social and political histories in context with the current privileging of memory over history

- post-memory; an expression introduced by Marianne Hirsch (2012) referring to secondary memory that has been constructed by the next generation rather than the primary

- enactment and re-enactment as relational or participatory forms of memory work

I will return to why the project This Is a Human Being should be placed among post-memory approaches.

Awareness and remembrance through drawing

Ignited by the question of how illustration can contribute to new ways of teaching and learning about the Holocaust, the project uses the act of drawing as a vehicle for developing civic awareness and memory-building. Rather than showing statistics and numbers, this project focuses on individual fates in order to provide young people with 'a way in' to the complexity of the Holocaust, through a rite of commemoration.

Participants arriving at a workshop receive a small parcel containing a stone wrapped in paper held together with a simple string. The paper contains information about the procedures of the workshop, including a number, and information about the historical context. Finally, a text informs one how, by taking part in a participatory workshop, one acknowledges that the material may be used in print or other forms of communication in later parts of the project.

“I wanted to enable a young person to see a person different from themself and reflect on that person’s personal history.”

On the wall of the workshop room is corresponding information about name, date of birth, gender, home address and in many cases—the date of deportation to the death camp in Chełmno. Following the drawing process, the stone is equipped with a nametag and placed according to the home address of each child on a big map on the floor. The drawings are exhibited on the wall. Finally, the participants are requested to respond to a survey, giving their opinion about procedures and outcomes. Each drawing is then reunited with its stone, and stored until a later stage.

Observations of the students in the first workshop in Łódz in 2016 revealed that for those of the students who had little previous knowledge the complexity of the Holocaust was difficult to grasp. I wanted to enable a young person to see a person different from themself and reflect on that person’s personal history. At this stage, the project is an investigation of how one might develop reflective and compassionate thinking 'through illustration'.

Data from the ghetto archive is used as source; a congratulatory protocol to Rumkowski on his birthday provided 14 587 signatures of school children and 715 teachers. This information is compared to different digitalized lists in the ghetto archives; population records, workplaces and a deportation list from spring 1942 (Archiwum Panstwowym 2013). Because of the difficulty of navigating the complex digital structure of the archive, knowledge of the Polish language is required to extract the wanted information. USHMM has used the same source material in an online project for young people (The Children of Lodz Research Project, 2008). If an individual’s identity is found in more than two lists, the information may be used in the project. Printouts with data about the individuals are hung on the wall.

A process of testing out design and procedures began with the first workshop on February 27, 2017. The second workshop took place in the Marek Edelman Dialogue Center in Łódz as part of the annual commemoration of the Holocaust victims in the end of August 2017. Workshop 3, also located in the Marek Edelman Dialogue Center, took place in October 2017. The stones, however, were given earlier, at Chełmno, as this workshop consisted of a group of cross-disciplinary students from the school network. As Workshop 4 took place on the International Holocaust Remembrance Day 27th of January 2018 at Falstad Centre in Mid-Norway, it was possible to apply the methodology to information from a Norwegian archive. Falstad provided this, in cooperation with the Jewish Museum in Trondheim, Norway. The identities used here were twenty people in the Trondheim area deported in 1942, representing different social and age groups. The final workshop took place at the Department of Design at the University of Bergen in March 2018, as part of a illustration seminar.

The content and methodology applied was the same as at Falstad. The participants were students from the Department of Design; eight women and one man, all in their early twenties. Norwegian was used in all information presented.

Participants in the project were asked a number of similar questions in all the different workshops.

Images that explain or elucidate information

Roland Barthes’ essay 'Rhetoric of the lmage' (Barthes, 1964) treats the image as a carrier of a system of signs; a linguistic message, a symbolic or connotated message and a literal, or denotated message.

Authors Gunnar Kress and Theo van Leeuwen (Kress og van Leeuwen, 2006) divide visual representations into two categories according to multi-modal theory: images that have a component of action—narrative representations (Kress and van Leeuwen, 2006, p. 45-78)—and those that possess a static, timeless essence—conceptual representations (Kress and van Leeuwen, 2006, p. 79−113). Narrative 'representations present unfolding actions and events, processes of change, and transitory spatial arrangements' (Kress and van Leeuwen, 2006, p. 59), while conceptual images representing participants in terms of their more generalized and more or less stable and timeless essence (Kress and van Leeuwen, 2006 p. 79).

In the introduction chapter to History of Illustration, the editors present a definition of illustration: Etymologically, the Latin root, lux, means 'to shine light upon'—to enable understanding. As an artwork, illustration is often expressive, personally inspired, and beautifully crafted, but unlike art for art’s sake, it is inherently in service of an idea and seeks to communicate something particular, usually to a specific audience. [ ... ] The 'what' (subject) and 'how' (medium) of an image are not the defining factors: rather, the 'why' (purpose) determines whether a work of art is illustration or not (Doyle, Grove og Sherman, 2018).

To interpret content, to transform verbal ideas into visual ones, students from the whole field of visual arts require training of critical reflection and visual intelligence. Therefor it is important to provide them with tasks during their studies that offer such possibilities, suggests educator and author Alan Male in his book Illustration: A Theoretical and Contextual Perspective: 'Illustration is the only discipline within the realm of visual arts and communications that explains or elucidates information. Much of what is seen by way of this contextual domain is the creation and interpretation of new knowledge', he claims (Male 2017, p. 119). He sees drawing as the principal faculty of illustration, and a way of informing the illustrator’s identity and developing and establishing one’s personal iconography. [ ... ] Observation and 'learning to see' is all part of the illustrator’s education. (Male 2017, p. 46).

Studying the drawings from this project, one may notice how some participants emphasize the contour, be it a firm contour left by felt nib in one continuous movement, or a pencil line varying and pausing, with different accentuation and pressure leaving different amount of graphite behind. Others put efforts into conveying the individual pattern of the stone. Defining light, shadow and three-dimensional form, is a third strategy. One drawing interestingly emphasizes the background surrounding the stone using black chalk, and in this way putting the stone in a symbolic context.

The stone drawings have no vectors that would create action as in distinctively narrative images. However, the scanty text found on the wrapping paper will act as an anchorage with the image, a code or a system of signs to be interpreted by the viewer.

Concluding the artistic research of the project

The discourse of methods in memory-building of Holocaust victims will continue, there is room for more voices joining. In the project This Is a Human Being, the drawings shed light on individual fates of the Litzmannstadt children. I claim all these approaches as reflected and compassionate visual thinking through illustration, in consistency to the theory presented.

After the last workshop in March 2018, a new direction was taken in the project. The next phase involves developing an artist book that conveys the idea. The stone drawings will live on as included elements in a sequential story about the children of Litzmannstadt ghetto. Merged with the visual expression of the panels in the story, the stone drawings and the names of the children will be brought on to the next generation. The stones are to be brought to a final destination at the Jewish cemetery as part of the annual commemoration in Łódz. However, understanding ‘the other’ is not just a matter of the past. To secure peaceful coexistence, we need attention and compassion for those in our surroundings in present and future. This is what my colleague Geir Goosen is doing in a parallel project that also takes place in Łódz. Joining forces under the title 'Palimpsest'6, our two projects are intertwined, related to this specific geographic place.

References

- Adorno, Theodor W,. Negative Dialectics. Londonand New York: Routledge, 1966.

- Adorno, Theodor W. "Cultural Criticism and Society." Prism , 1983: 34.

- Altomonte, Jenna A. The Postmemory Paradigm: Christian Boltanski’s Second-Generation Archive. June 2009. https://etd.ohiolink.edu/rws_etd/document/get/ohiou1244047774/inline (accessed August 18, 2018).

- Archiwum Państwowym, w Łodzi and Urzędem Miasta,. "WIRTUALNE MUZEUM DZIEDZICTWO ŻYDÓW ŁÓDZKICH." http://museum.lodzjews.org. -- --, 2013. http://museum.lodzjews.org/en/41-%E2%80%9Ewielka-szpera%E2%80%9D-general-curfew (accessed 03 01, 2018).

- Barthes, Roland. Rhetoric of the Image. Edited by Ed. and trans. Stephen Heath. New York: Hill and Wang, 1964.

- Baudrillard, Jean. "Holocaust." In Simulacra and Simulations, 49. Chicago: University of Michigan Press , 1987.

- Celan, Paul. "Fugue of Death." poets.org. Edited by Jeffrey Pain. -- --, 2000. https://www.poets.org/poetsorg/poem/fugue-death (accessed 03 05, 2018).

- Chronik des Gettos. http://www.ghettochronik.de/de/impressum. 2009-2011. http://www.ghettochronik.de/pl (accessed 03 01, 2018).

- Doyle, Susan, Jaleen Grove, and Whitney Sherman. History of Illustration. 1.utgave. New York: Bloomsbury Publishing, 2018.

- Gibbons, Joan. Contemporary Art and Memory: Images of Recollection and Remembrance. 2.utgave. 2012.

- Guggenheim. Guggenheim Collection Online. https://www.guggenheim.org/artwork/artist/christian-boltanski (accessed 08 18, 2018).

- Holocaust Research Project. "holocaustresearchproject.org." Edited by Carmelo Lisciotto. -- --, 2007. http://www.holocaustresearchproject.org/ghettos/rumkowski.html (accessed 03 01, 2018).

- Horwitz, Gordon J. Ghettostadt. 1. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press, 2009.

- Kress, Gunther, and Theo van Leeuwen. Reading Imgaes. The Grammar of Visual Design . 2nd. London and New York: Routlegde, 2006.

- Kristeva, Julia. Powers of Horror: An Essay on Abjection . 1982.

- Krznaric, Roman. Empathy: Why It Matters and How to Get It. Perigee, 2014.

- Löfström, Erika, and Anna Nevgi. "Giving shape and form to emotion: using drawings to identify emotions in university teaching." 7 22, 2013. https://doi.org/10.1080/1360144X.2013.819553 (accessed 08 19, 2018).

- Laub, Dori. "Truth and Testimony: The Process and the Struggle." In Trauma. Explorations in Memory, edited by Cathy Caruth. Baltimore: The John Hopkins University Library, 1995.

- Levi, Primo. "If This Is a Man." In The Complete Works of Primo Levi. London: Penguin Classics, 2015.

- Male, Alan. Illustration: A Theoretical and Contextual Perspective. 2.utgave. New York: Bloomsbury Visual Arts, 2017.

- Montague, Patrick. Chełmno and the Holocaust: The History of Hitler's First Death Camp. 1.edition. North Hill: The University of North Carolina, 2012.

- Nussbaum, Martha C. Cultivating Humanity. 7. Vol. 2003. Cambrigde, Massachusettes: Harvard University Press, 1997.

- Spiegelman, Art. Maus. Pantheon Books, 1980-1991.

- The Children of Lodz Research Project. The Children of Lodz Research Project. United States Memorial. 2008. https://www.ushmm.org/online/lodzchildren/ Retrieved 2018-02-27 (accessed 03 01, 2018).